The ouroboros is an ancient symbol depicting a snake or dragon eating its own tail. Ouroboros traditionally symbolize the eternal life cycle: birth, death, rebirth. Unlike many ancient symbols, though, a snake eating itself is a real thing. Also, unlike the beautiful symbolism of ouroboros, the real event in nature is not so pretty.

You can find videos online of snakes eating themselves, though I don't recommend it (especially if, like me, snakes creep you out). I'll spare you the twisted visuals (pun intended) and tell you what happens: Since snakes require external conditions to manage their body temperature, sometimes they get overheated. Overheating can lead to disorientation and a false sense of hunger as metabolism speeds up. This wicked combination can cause a snake to mistake its own tail for prey. The snake latches onto its tail and starts digesting—a process hard for a snake to stop on its own. Unless someone changes the environment—cooling it down or intervening with a veterinarian—the snake kills itself. Oof.

While a snake eating itself in nature isn't very common, an analogous process happens all the time in schools. Here's what it looks like:

Educators at all levels experience excessive workloads, which lead to greater burnout and less productivity. As performance dips, pressure picks up—affecting students, teachers, and school leaders. This high-pressure "body heat" of the school gets out of control, prompting school leaders to target the character and work effort of their own staff (the snake's tail) rather than the context of the working conditions (the real threat). So, we lash out with a self-sabotaging action called micromanagement. We think that controlling, dictating, and demanding more will force educators to step up. We replace trust and agency with scripted curriculum and reduced choices. However, this only adds to the pressure, exhaustion, and burnout. And the cycle continues.

Gross, snake-eating-itself analogy aside, there's real data on the devastating effects of tightening control on workers. Micromanagement is associated with lower morale, higher turnover, and reduced productivity. Those who experience burnout are three times as likely to feel micromanaged (Collins & Collins, 2002). One study found that 63 percent of educators felt micromanaged in the last week (Rogers et al., 2021). Micromanagement can also be a two-hit punch to the gut: (1) Talented teachers reject micromanagement to opt for different jobs or careers and (2) micromanaging policies erode autonomy, reducing personal responsibility for one's work (Hargreaves, 2003). Rather than releasing the pressure by giving educators more agency and choice, schools choke on their own pressures of control.

If we want education to be a desirable profession, then we must treat educators as professionals, breaking the cycle of exhaustion and pressure that creates distressed, burned-out educators. Yet releasing control doesn't mean coddling conditions or work-when-you-want chaos. It means giving teachers agency, especially over their daily decisions and biggest workloads.

What would happen if, rather than pressuring teachers to do more teaching, grading, and testing, we gave them the freedom to do less?

Reduced Workload, Increased Agency

After 15 years as a classroom teacher, instructional coach, trainer, and consultant, I've realized that these three tasks are the most burdensome parts of educators' workloads:

Lesson planning

Grading/feedback

Data monitoring

Not only are these often our biggest time sucks, they are also the areas that tend to get micromanaged. When the pressure to perform increases, educators are dictated what, when, and how to teach and assess. When schools attempt to make gains, they pile on more rather than less—more scripted curriculum, more lessons within a day, more assessments, more restrictions on autonomy.

So, what would happen if, rather than pressuring teachers to do more teaching, grading, and testing, we gave teachers the freedom to do less? In 2020, the United Kingdom's Department for Education released results from a massive controlled study that attempted to answer that question. Administered across eight regions, the study involved dozens of schools, hundreds of educators, and nearly 11,000 students. Schools hosted controlled, longitudinal studies, testing a variety of practices to reduce workload, while increasing educator agency and well-being—all while tracking effects on student performance.

In total, the research team was able to do a meta-analysis of 112 workload-reduction interventions, testing strategies related to feedback practices (e.g., having students grade their own work in the moment); peer grading (e.g., whole-class verbal feedback); data monitoring (e.g., reducing the frequency of data collection); and lesson planning (e.g., simplifying lesson planning sheets).

Among the many surprises of these studies ("Whoa … a national department of education actively sought to reduce teacher workload and increase teacher agency and well-being!?"), there are three that are most significant:

The interventions reduced the average additional teacher work time (that is, time spent working beyond contractual hours) from 1 hour and 20 minutes per day to 30 minutes per day.

Reducing workload consistently boosted teacher well-being, decreasing feelings of workaholism and increasing self-efficacy, optimism, love of learning, and enthusiasm.

Reducing the workload consistently had either no effect or a positive effect on student performance (Churches, 2020).

That's right: At worst, empowering educators to decrease their workload had zero effect on student achievement. At best, students actually improved their performance as they experienced efficiencies like more specific, immediate feedback; more time learning and practicing content as opposed to weekly testing; and less stressed and overworked teachers.

So maybe if we want better outcomes, we need to let go of the controls and pressure that are choking teachers, preventing them from getting better outcomes.

For now, education is eating itself. In our push for relentless improvement, we target the wrong source. We pile pressure and workload and expectations onto the most critical piece of this profession: The professionals themselves. If we want to truly make education a desirable job, we have to let go. Let go of the control. Let go of the micromanagement. Let go of adding more work and pressure and mandates. Because the only thing we need more of is respect as professionals. More trust. More voice. More choice.

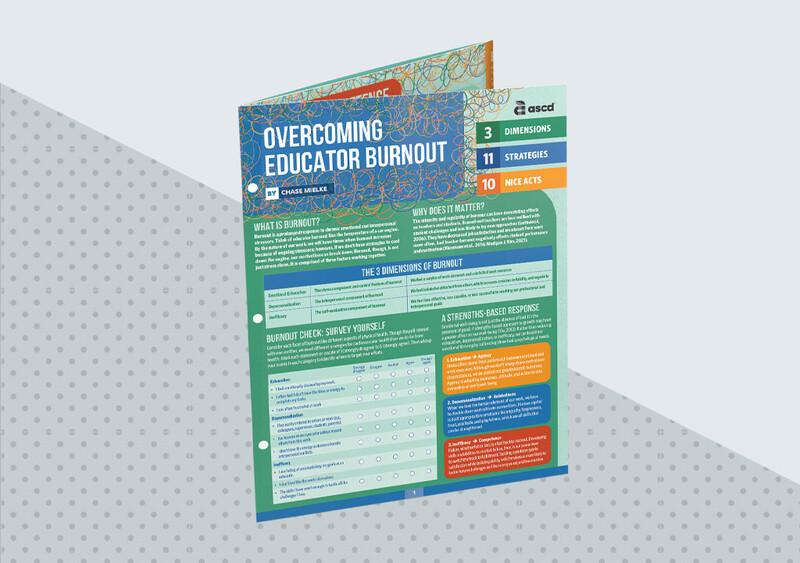

Overcoming Educator Burnout (QRG)

In this Quick Reference Guide, Chase Mielke identifies the factors most likely to lead to burnout and how to combat them in your everyday work life.