March 1, 2023

•

•

Vol. 80•

No. 6Richard Culatta on the “Transitional Moment” in Education

This is not the time to revert to what's comfortable but not effective or equitable, says new ASCD-ISTE CEO.

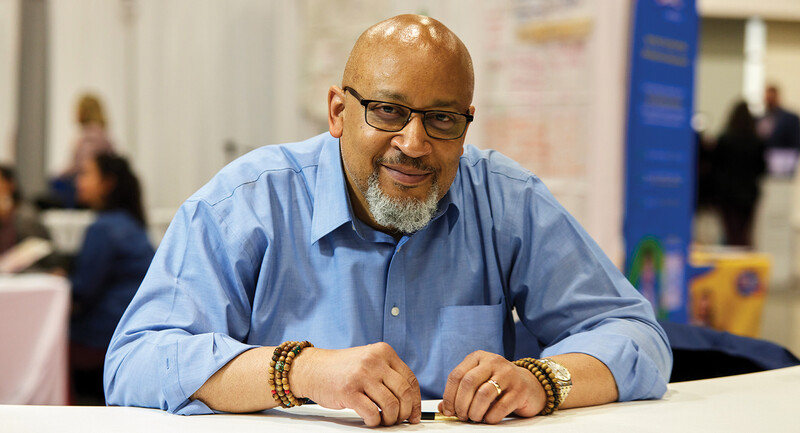

Credit: STEVE SMITH PHOTOGRAPHY

Richard Culatta has been the chief executive officer at the International Society for Technology in Education for six years—and is now also the CEO of ASCD, after its recent merger with ISTE. Prior to joining ISTE, he was the chief innovation officer for the state of Rhode Island and director of the U.S. Department of Education's Office of Educational Technology. A former classroom teacher, he is also the author of Digital for Good: Raising Kids to Thrive in an Online World (Harvard Business Review Press, 2021). In all these capacities, Culatta has had a deep interest in the role of innovation and change in education and has guided many transformational-change initiatives. We recently talked to him about leading through change at the current, post-pandemic juncture in education.

One of the things that we should all ask ourselves is, "What are the practices that I'm doing because they've become comfortable and what are the practices that I'm doing because they're really the most effective?" During the height of the pandemic, we were all pushed way beyond our comfort zone. But now that we're returning to what feels a little more like a normal school year, I worry a bit that we are reverting to practices that feel comfortable but aren't necessarily effective. So I keep trying to remind myself that comfortable and familiar is not the same as effective and equitable. For me, it's about continually asking, "Is this the best way? Given the changes in resources, technology, and experiences that we've all had over these last couple of years, is this approach I'm taking really the most useful?"

This certainly applies to the work we do at ASCD and ISTE in providing professional learning for educators and helping districts develop compelling visions for how they are going to use the technology that is now available to them. How do we ensure we aren't falling into old patterns just because they are familiar? We need to adapt to new circumstances and new possibilities, to bridge technology advances and educators' changing needs and goals. This was the spark that started the merger with ASCD in the first place: We realized that, in this new world, conversations around technology and innovation cannot be separate from conversations around effective and inclusive learning.

I think of "changemakers" as the type of people that this new joint organization is looking to serve. To me, a changemaker is somebody who is not satisfied with the status quo when the status quo is not serving students and educators well—and who is also smart enough to know the difference. That is, if there are things in place that are working well, we're not going to change them just for the sake of change. It's someone who recognizes what's working and what's not working. And when something's not working, a changemaker is the person who's bold enough to say, "We're going to do something about this."

These are the people who are ASCD and ISTE's core community, whether that's a superintendent, a chief academic officer, a head of instructional technology, or a teacher. In some cases, it could also be somebody who is designing a new tool or product to support learning. Changemakers are the people who see opportunities to make significant improvements upon the status quo. These are the people who say, "We see an opportunity to make a significant improvement upon the status quo." We want to help support them in doing that: That's the goal of this new combined organization—it's about supporting people who are leading smart, impactful change in education.

I think the most important thing is to realize that technology has the power to be an accelerator: It accelerates whatever we apply it to. So if we're applying it to practices that we know are solid, that align with inclusive and effective pedagogy, it will accelerate those practices. But if it's applied to practices that are not effective—like pushing static content to students—it will accelerate those practices as well. What we saw during the pandemic was a massive adoption of technology without a fundamental shift in the learning approach or learning vision, because there wasn't time for that level of preparation. To be clear, a great many educators made heroic efforts to shift to online learning in a very short amount of time in order to just keep some continuity for their students. But this was emergency remote learning, which is not the same as effective digital learning.

The COVID-instigated online learning experience wasn't optimal for many students and teachers. But it has created an amazing opportunity to set a better course now. Because of what we have just gone through, we have access to better connectivity, to better devices, to better software and technology support in many cases. And now it's our role as education leaders to say, "How do we use these tools for more than getting us through an emergency? How do we use them to create transformative learning experiences?" That's the end goal—not just to use tech to do what we were doing before (except on a screen) but to enhance and accelerate what we know are best practices in instruction.

It's important to recognize how much the education community has been through in these last couple of years and that teachers are exhausted. Leaders are exhausted, too. At the same time, the world has changed, the world around us has evolved, and education is not exempt from needing to evolve as well. We've certainly tried to model that with the move to bring ASCD and ISTE together. We recognize that what education leaders need for the future looks different than what they needed three years ago. We also can't let this very important transitional moment go to waste. We have the best chance to reset and redesign the future of learning that we've seen in decades. If we just go back to what we were doing before, it would be a huge missed opportunity. But if we can leverage this moment to say, "Well, maybe this wasn't how we wanted to get here, but we're going to use this opportunity to rethink some practices in education that were never very effective or inclusive," then I think we can grow as a result of our experiences in the pandemic.

Boy, do I ever! I could go on a long time about this. But the quick, simple answer is, schools need to be really thoughtful about the conditions they're setting for tech use. When I visit schools, one of the things I ask, because I'm a geek, is to see their acceptable use policy for technology. And a lot of those policies feel like a big list of don'ts. It's all about the things not to do with technology—don't cheat, don't be mean, don't share your password, don't waste time. It's all negatives: don't, don't, don't. The challenge with this is that learning to be a healthy member of the digital world is a complex skill. Learning any complex skill takes practice, and you can't practice by not doing something. So it's critical for schools to flip this model: We need to articulate what the digital competencies are that we want young people to practice and to model those behaviors as the adults in the system. If we can just shift to clearly articulating the dos, we will be much more successful in terms of preparing young people to thrive in our digital world.

Absolutely! I do love spending time in schools—whenever I'm traveling, I try to schedule a school visit. One consistent innovation I'm seeing is the demise of a myth we've long held onto in education that access to expertise is limited by the physical location of the school. If the pandemic has taught us anything in terms of learning, it's that physical location shouldn't be a limitation. No matter where your school is, you should be able to tap into experts anywhere in the world. At a school in Los Angeles, I saw students leveraging connectivity to engage with local political leaders to explore ways to make their neighborhood cleaner. In a school in Newport News, Virginia, there was a teacher who arranged for her students, as part of their learning about ecosystems, to "go along on" a safari as it was live-streamed from Africa. And these kids weren't just watching videos—in both cases, students were engaging with experts and experiences.

The pandemic also reminded us that we can't learn effectively in isolation. Effective learning doesn't start and stop at the door to the classroom. We need to have parents engaged and involved. We need to have community organizations engaged and involved. I've loved seeing examples of how schools have come back after COVID and maintained and leveraged some of their great community connections. I was recently visiting schools in Middletown, Ohio, where they've done a fantastic job of this. One school partnered with a STEM organization to create an aviation program for kids to learn the mechanics of airplanes and even learn to fly. This is a great example of opening up possibilities that would never happen if we accepted that all learning was bound by the classroom walls.

I think one of the challenges is to recognize that to be effective, technology must always be in the service of learning. That means it is the instructional leaders who need to set the vision and the expectations for how technology is used in a school or district. With all the things that instructional leaders are dealing with, it's easy to let that role get delegated to somebody else—for example, to the chief information officer or IT staff. And while the chief innovation officer or other administrator in a tech-focused role should be a great partner to any instructional leader, it has to be the instructional leader that sets the vision for how technology is going to be used for learning. If you don't do that, you're in a textbook 'cart-before-the-horse' scenario. That's my biggest warning: Be clear about the learning vision and then ensure that the use of technology is supporting that vision, not the other way around. Getting this right can have a major impact on the success of an entire school or district.

I'm hopeful because educators as a whole are some of the most creative professionals I've ever seen in any industry. That's a huge asset at a time when we have to be open to thinking differently. Historically, after a period of chaos and trauma, there's always a bloom of innovation because people are more willing to try some new things and try to solve problems. We currently have conditions that are ripe for positive innovation in education, and I'm very excited about what we can accomplish over the next few years.

We need to keep some things in mind as we move forward, though. One of them is them is that learning has to feel joyful. I am concerned about that as more and more data comes out showing us how far behind students are. This can lead to a gut response to double down on drill-and-kill type practices, and because we are dealing with a serious problem, to respond in a very serious way. But when that happens, we risk losing the joy that is so critical to addressing these very problems. So I think we need an infusion of joy in our learning systems. Schools should be joyful places. Teachers should feel joy about the work that they're doing.

When I meet with school leaders, I often challenge them to think about what they are doing to increase joy in their buildings. That's a key role that may not be the first thing that comes to mind for an education leader—but I believe it is critical for helping us recover from the challenges of these last few years. To borrow a concept from the tech world, it has never been more important to make sure you are creating an amazing user experience in your school.

Editor's note: This interview has been edited for space.